Nigerian-Canadian designer Lani Adeoye has written a wonderful essay on design in Africa for the “White Book".

Before you’ll read excerpts from it here, we would like to set the mood with a quote that Lani Adeoye very much appreciates. It is from Lagos-based creative director Papa Omotayo:

“(...) Design as a term in Africa should just be a placeholder. I don’t think it speaks to the totality of our intentions here. Design to me has always seemed very linear ever since I moved back to Nigeria. Here, there is always a sense of renewing, repurposing, reinvention – something interconnected within our consciousness, which feels pre-design. A fullness in our ability to hold so many layers of truths both spiritually and rationally."

Enjoy diving into Lani’s experiences and thoughts!

Culture before and after design

By Lani Adeoye

As a designer, my cultural identity is crucial in terms of how I express myself both consciously and sub-consciously, in particular through my furniture design studio, Studio-Lani. I believe the objects we surround ourselves with embody intangible values that reflect what we believe and what we appreciate at that specific time. Having lived in four major cities, Lagos, Montreal, Toronto and New York, I’ve witnessed how the DNA of a community molds its design culture and subsequently its output. (...)

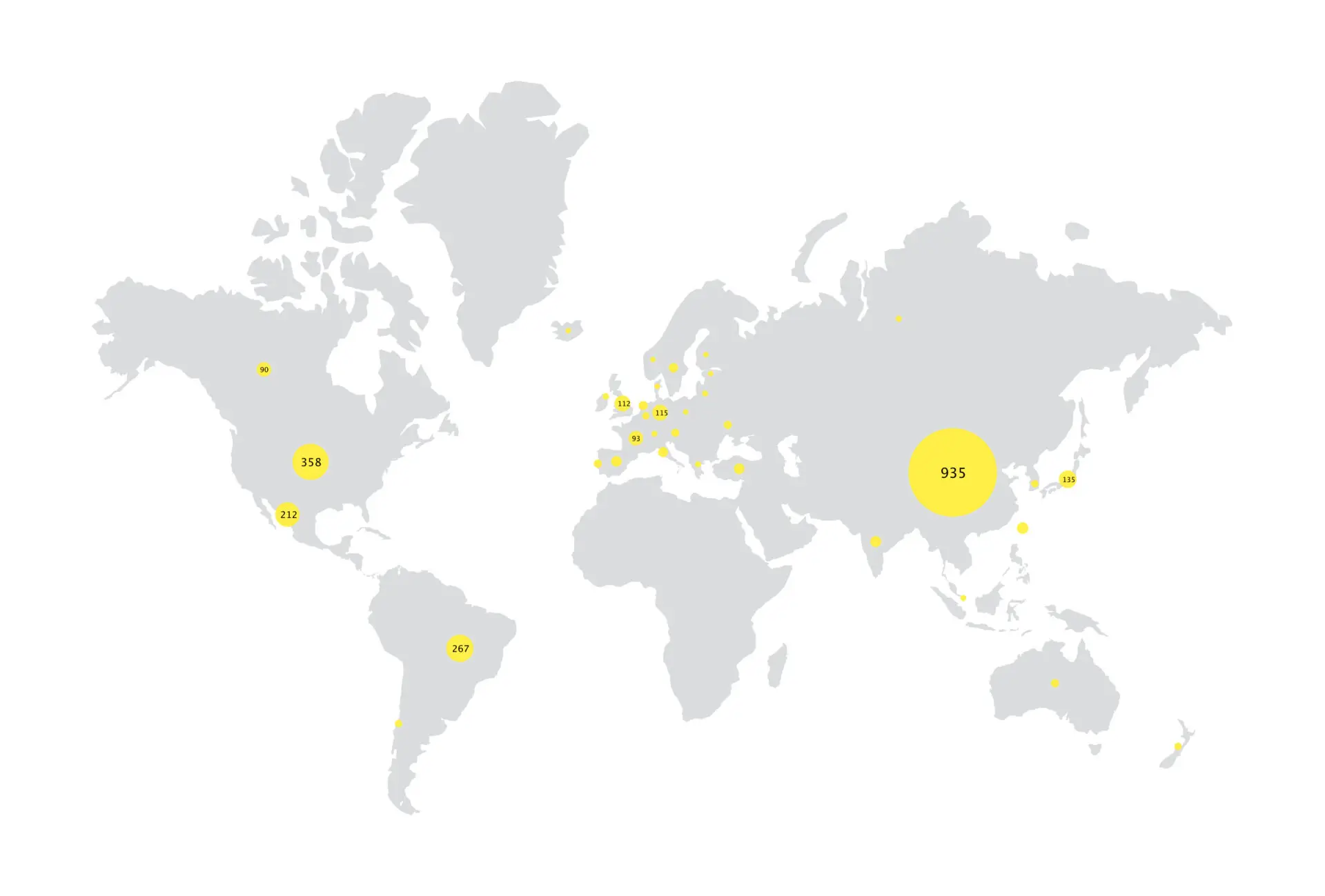

Diverse context gives birth to diverse content

We run the risk of telling a highly skewed story if we lump various African countries into one template. Africa is a vast continent, inhabited by an estimated 1.275.920.972 people, home to 54 countries, and with an estimated 3.000 different native languages. Therefore, we cannot limit. its story to a single narrative, which is often the common default. Although there are commonalities in various parts of Africa, we shall try to avoid generalization and refrain from amplifying that monolithic story. I have therefore chosen to focus predominantly on one country, Nigeria. Nigeria is West Africa’s most populous country; with an estimated 206 million inhabitants as of late 2019. Nigeria is quite multicultural, home to more than 250 ethnic groups with over 500 distinct languages, each with its own cultural identities. I share this information by way of prefacing the following pages in order to explain how multilayered and diverse just one country can be. (...)

The past creates the present

Design is influenced by culture, and since culture is a direct reflection of history, we cannot separate the connection between a country’s history and its creative output. Before I delve into my Lagos findings, it would be remiss if I did not touch on the impact slavery and colonialism have had on robbing Africa of its true glory. Not only did it affect the way African countries are viewed by the world, it also left Black people around the world to deal with the mental repercussions. Fela Kuti from Nigeria, who was a revolutionary musician, spoke about this notion in his songs, expressing the devastating after-effect it had on us mentally. Furthermore, most information about African countries in circulation was created by non-Africans and often depicts Africans as inferior, which serves to further the negative stereotypes. Unfortunately, this has placed Black people at an enormous disadvantage in terms of truly learning about African history and seeing it from an authentic stance. However, various historical and cultural movements have strongly encouraged Black & African pride, creating a more empowered state of mind which challenges the status quo and seeks to redefine our narrative through our own perspective.

Art and culture in design

To fully comprehend the concept of design within the Nigerian context, one has to first understand its interconnectedness with art from a cultural vantage point. For many cultures within Nigeria, historically art was created to serve a purpose, i.e., it was not made merely for aesthetic or decorative reasons. It was often related to an activity or ceremony, and told stories. From the intricately carved wooden stools to carved masks, there was often something symbolic attached to objects. One can infer that artists operated in the capacity of designers by creating purposeful objects that also offered aesthetic value. Expressing ourselves creatively has always been a way of life and art was integrated into many facets of life. Nigerian textiles demonstrate this notion of symbolic art and design as a means of communication.

Adire Eleko is a type of textile design unique to the Yoruba culture in southwest Nigeria; this craft has been around since 1910. Traditionally, women dyed the cloths and designed the motifs for the textiles. Textiles reflected the identity of a tribe and allowed different communities to differentiate each other. The motifs on the textiles were symbolic and were used to convey a message or historical event. For example, the cowry icon signified money, earrings represented hearing good news, the mirror symbol represents someone who is a reflection in your life.

Aside from what we wore, how we did our hair was also connected to cultural expression and was often deeper than just the aesthetic appeal. »In the early 15th century, hair served as a medium of messages in most West African societies. Africans – citizens from the Mende, Wolof, Yoruba, and Mandingo – were all transported to the »New World« on slave ships. Within these communities, hair often communicated age, marital status, ethnic identity, religion, wealth, and rank in the community«. (Tharps & Byrd, 2001)

Furthermore, hair was also used as a tool to share specific information during slavery. For example, cornrows were braided in map patterns that illustrated routes to freedom and also indicated someone’s intention so others could help as necessary. This was a coded way for Africans to communicate among themselves without their masters understanding the plan of action. Most notably, Benkos Bioho, who escaped slavery, created his own intelligence network and asked women to create maps through their cornrows to help deliver messages. Since slaves were often banned from reading and writing, finding more discreet ways to send survival messages was extremely important. For instance, slaves in Colombia would braid a hairstyle called »departs« when they wanted to escape; the cornrows would be braided into buns at the center of their head. Curved braids sometimes indicated the recommended escape routes to follow. Furthermore, braids were also used for survival, to store gold and seeds to provide resources for people once they escaped. (...)

Editor’s note: Later in the essay, Lani Adeoye introduces the personal perspectives of other Nigerian designers. You can read about them “Designing Design Education – White Paper on the Future of Design Teaching”